In the Science Section of today's New Duranty Times, Nicholas Wade authors a report on this article by Steven Kuhn and Mary Stiner of the University of Arizona posted online at the journal "Current Anthropology."

They argue that the reason that Neanderthal man disappeared was that Neanderthals did not divide different types of work between men and women, but that Neanderthal women hunted large ungulate game animals alongside Neanderthal men. This way of life was less efficient than the way the ancestors of modern man lived, with the men out hunting while the women gathered plants and small animals. The more efficient economic way of life of the ancestors of modern man gave them a big demographic advantage.

The problem with this type of theorizing is that the data that support it are very tenuous, at best. Kuhn and Stiner base their theory on the absence of bone awls and needles from Neanderthal sites. They assume that the bone awls and needles found at sites associated with the ancestors of modern man were used, by women, to fabricate clothing.

If you think about it, even if you accept the unproven assertion that the bone awls and needles were used to fabricate clothing, their absence from Neanderthal sites does not necessarily prove that Neanderthals did not have a sex-based division of labor.

Maybe they just didn't know how to sew.

There is, however, a far more telling absence from the archeological sites presumed to be inhabited by Neanderthal man: there is no evidence there of the domesticated dog. John Allman of Cal Tech suggests that it was the domestication of the dog that gave the ancestors of modern man such an advantage over the Neanderthals.

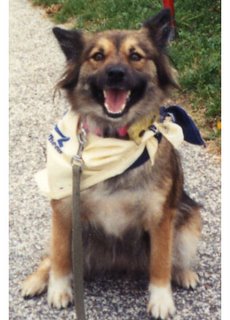

I'd put it somewhat differently. It was the dog's domestication of the ancestors of modern man that enabled them to become what we are, today. By sharing their gifts of keen eyesight, preternatural olfaction, and superb social organization with anthropoids who had opposable thumbs and who could communicate with speech, the ancestors of the modern dog enabled the eventual flowering of human culture.

They argue that the reason that Neanderthal man disappeared was that Neanderthals did not divide different types of work between men and women, but that Neanderthal women hunted large ungulate game animals alongside Neanderthal men. This way of life was less efficient than the way the ancestors of modern man lived, with the men out hunting while the women gathered plants and small animals. The more efficient economic way of life of the ancestors of modern man gave them a big demographic advantage.

The problem with this type of theorizing is that the data that support it are very tenuous, at best. Kuhn and Stiner base their theory on the absence of bone awls and needles from Neanderthal sites. They assume that the bone awls and needles found at sites associated with the ancestors of modern man were used, by women, to fabricate clothing.

If you think about it, even if you accept the unproven assertion that the bone awls and needles were used to fabricate clothing, their absence from Neanderthal sites does not necessarily prove that Neanderthals did not have a sex-based division of labor.

Maybe they just didn't know how to sew.

There is, however, a far more telling absence from the archeological sites presumed to be inhabited by Neanderthal man: there is no evidence there of the domesticated dog. John Allman of Cal Tech suggests that it was the domestication of the dog that gave the ancestors of modern man such an advantage over the Neanderthals.

I'd put it somewhat differently. It was the dog's domestication of the ancestors of modern man that enabled them to become what we are, today. By sharing their gifts of keen eyesight, preternatural olfaction, and superb social organization with anthropoids who had opposable thumbs and who could communicate with speech, the ancestors of the modern dog enabled the eventual flowering of human culture.

No comments:

Post a Comment