First, President Clinton should secure the nation's borders and in the process help the urban poor for a change -- by sending all those who repeatedly hire illegals to jail.

Second, he should remain resolute in his commitment to welfare reform, but find the means to reduce adult dependency without increasing childhood misery.

Third, he should always remember that Presidents earn the mantle of greatness, not by doing many things competently, or by being politically unsinkable, but by doing one or two great deeds out of moral conviction and by sheer force of will.

But this week, turning his attention to international policy, peace and war, Professor Patterson gets it all wrong.

Following the big-lie propaganda-line of the hard left, he first advances the mendacious claim that President Bush's emphasis on bringing freedom to the oppressed Iraqi people was a late bait-&-switch:

Once President Bush was beguiled by this argument he began to sound like a late-blooming schoolboy who had just discovered John Locke, the 17th-century founder of liberalism. In his second inaugural speech, Mr. Bush declared “complete confidence in the eventual triumph of freedom ... because freedom is the permanent hope of mankind, the hunger in dark places, the longing of the soul.”

Patterson then repeats the oft-heard claim that the more highly pigmented races of man don 't know what it means to be free, and don't necessarily like freedom when they meet it:

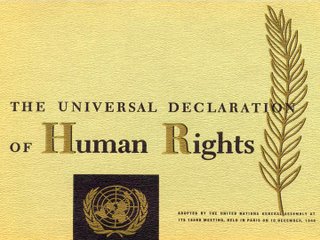

Those of us who cherish liberty hold as part of the rhetoric that it is “written in our heart,” an essential part of our humanity. It is among the first civic lessons that we teach our children. But such legitimizing rhetoric should not blind us to the fact that freedom is neither instinctive nor universally desired, and that most of the world’s peoples have found so little need to express it that their indigenous languages did not even have a word for it before Western contact. It is, instead, a distinctive product of Western civilization, crafted through the centuries from its contingent social and political struggles and secular reflections, as well as its religious doctrines and conflicts.

But his biggest mistake is to think that the tyrants of the world, who rule their peoples through the cruelty of democide, can be dislodged without the conflict that even Thomas Jefferson knew would always be required:

Acknowledging the Western social origins of freedom in no way implies that we abandon the effort to make it universal. We do so, however, not at the point of a gun but by persuasion — through diplomacy, intercultural conversation and public reason, encouraged, where necessary, with material incentives. From this can emerge a global regime wherein freedom is embraced as the best norm and practice for private life and government.

Acknowledging the Western social origins of freedom in no way implies that we abandon the effort to make it universal. We do so, however, not at the point of a gun but by persuasion — through diplomacy, intercultural conversation and public reason, encouraged, where necessary, with material incentives. From this can emerge a global regime wherein freedom is embraced as the best norm and practice for private life and government.

The best you can say about this advice is that it is fatuous.

Sure, there have always been many who advocated such "intercultural conversation."

Sure, there have always been many who advocated such "intercultural conversation."

The Copperheads and the Peace Democrats urged it on Abraham Lincoln.

But, if Abraham Lincoln had agreed to respond to the secession of the slave-holding states with mere diplomacy, persuasion, and "intercultural conversation," then slaves across the South would be picking cotton still.

Lincoln's attitude was altogether different. In the Second Inaugural Address, he put it this way:

Lincoln's attitude was altogether different. In the Second Inaugural Address, he put it this way:

Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away.

Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether."

Like Professor Patterson, the Punditarian hopes that the mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away from the marshes, deserts, and mountains of Iraq.

But enduring that scourge is still preferable to abandoning the Iraqi people to the perpetual violence of tyrants, fanatics, and criminals.

GULF NEWS DAILY:

GULF NEWS DAILY: